How the Ukrainian language is protected today - an interview with the Commissioner for the Protection of the State Language

Kyiv • UNN

Olena Ivanovska, Commissioner for the Protection of the State Language, spoke about the mechanisms for protecting the Ukrainian language, the number of citizens' appeals and responsibility for violating language legislation.

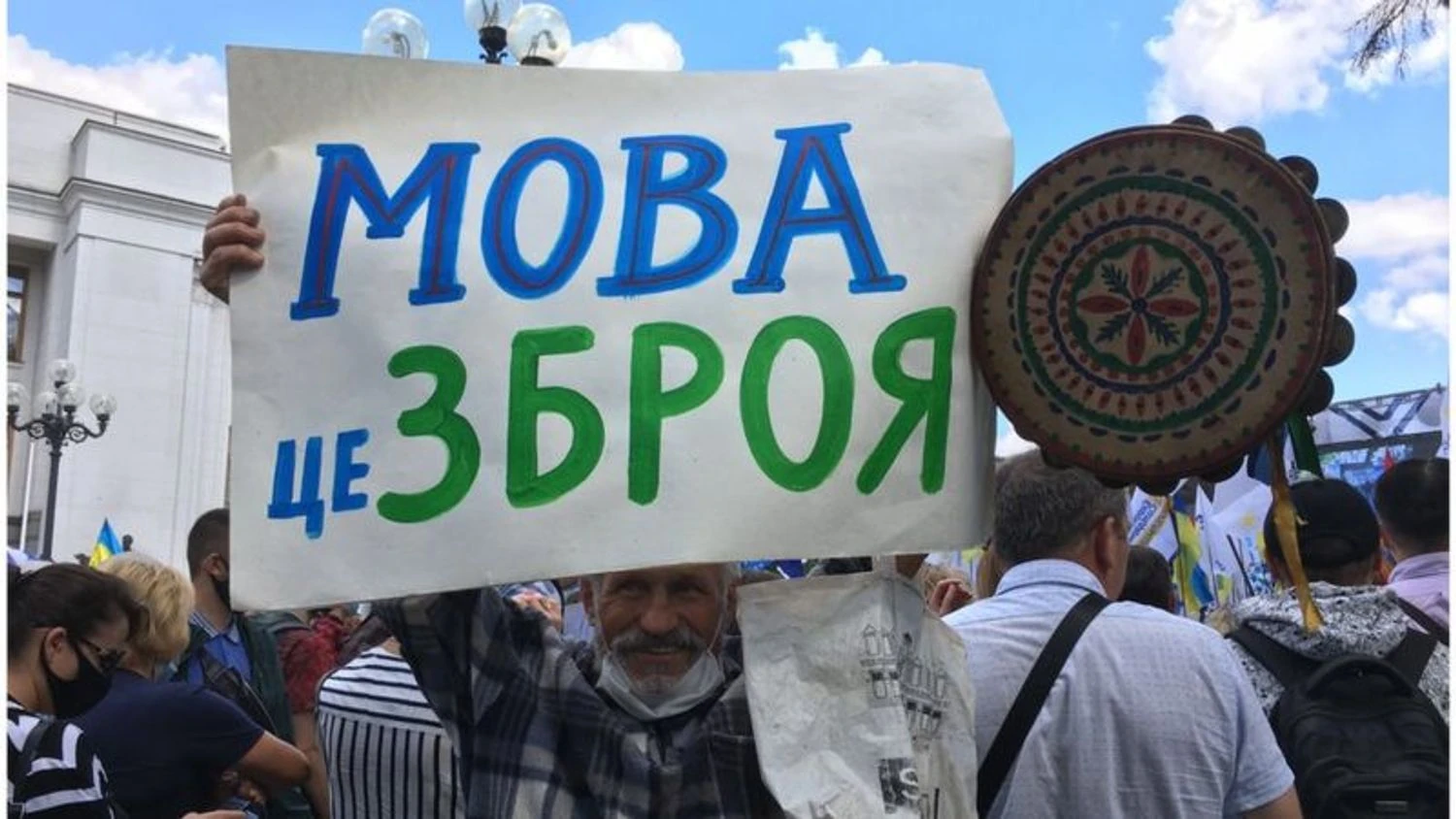

The issue of protecting the Ukrainian language has always remained a painful and at the same time vital one for our state. It became especially acute after the start of the full-scale invasion of the Russian Federation. The invaders immediately showed their true goal — not only to destroy cities, but also to erase the Ukrainian language wherever they appear. Mariupol was still holding its defense, but Russian utility workers were already replacing road signs, demonstrating their zeal. Therefore, today the issue of protecting the Ukrainian language in free territories is no longer a matter of culture, but a matter of national survival.

How does the state actually protect the Ukrainian language? Are there mechanisms that turn law into an effective tool? Can one be punished for refusing to serve in Ukrainian? How does society react to this? And should one be afraid of "language patrols"? UNN correspondent spoke about this with the Commissioner for the Protection of the State Language, Olena Ivanovska.

– How does the Commissioner's Secretariat respond to citizens' appeals regarding the violation of their language rights? How many such appeals are received monthly?

Citizens' language appeals are a kind of barometer of the country's language life. In October 2025, the Commissioner's Secretariat received 272 appeals, in September — 294. Since the beginning of the year, we have already registered 2499 complaints regarding violations of the Law of Ukraine "On Ensuring the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language". This is a consistently high indicator, which indicates the main thing: Ukrainians are not indifferent to the language, they want to live in a space where Ukrainian sounds natural and dignified.

We carefully consider each appeal. We clarify the circumstances, send requests to institutions or enterprises where the violation occurred. If the fact is confirmed, the Commissioner's representative carries out state control. We demand the elimination of the violation, provide explanations or draw up a protocol on administrative responsibility.

But the essence of our work is not in punishment, but in fostering a legal culture. We want people to understand that communicating in the state language is not a formality, but a sign of respect for the law and for oneself. We also work in the communication field. On the Commissioner's Facebook page, examples regularly appear where, thanks to the indifference of citizens, the situation can be changed. For example, after our intervention, a Kyiv coffee shop created a full-fledged Ukrainian-language version of its website, and a private clinic in Kharkiv resumed the practice of serving patients in Ukrainian.

Such stories convince us: the law sets the framework, but real changes are created by people — those who do not remain silent and defend their right to hear Ukrainian in education, medicine, service, and advertising. It is pleasant to see that not only the number of appeals is growing, but also their quality: citizens are increasingly better acquainted with the law, refer to specific articles, and are oriented in protection mechanisms.

– What responsibility is provided for establishments that refuse to serve in Ukrainian?

The law clearly states: every citizen has the right to receive information and services in Ukrainian. This is part of our civic dignity. If an establishment serves in another language without the client's consent, it is a violation.

Responsibility is provided for by Article 188-52 of the Code of Ukraine on Administrative Offenses. Thus, recently in Kharkiv, a taxi driver was fined 5100 hryvnias for refusing to serve a passenger in Ukrainian. The company reacted immediately — the driver was blocked, and all employees were reminded of the mandatory use of the state language in communication with clients.

But our goal is not fines. We aim to change the habit instilled by decades of foreign language dominance. Today, Ukrainian society is increasingly less tolerant of the remnants of colonial linguistic inertia. People want change — and we must give them effective tools.

The best result is achieved through explanatory work. When an establishment itself updates its standards, introduces Ukrainian-language service, and conducts briefings for staff — that is a real victory. We support such initiatives, because the Ukrainian language is not a burden, but a resource of trust and a competitive advantage.

In wartime conditions, when the enemy continues the policy of "denazification" aimed at destroying Ukrainian identity, language legislation needs strengthening, and the institution of the Commissioner needs personnel reinforcement. We must guarantee every citizen the right to receive information and services in the state language.

Language habits are formed from childhood. But it is educational institutions, from kindergarten to university, that must foster language resilience. Unfortunately, according to the latest surveys conducted jointly with the State Service for Education Quality, a decrease in the level of communication in Ukrainian by 10% was recorded in Kyiv schools.

In autumn, the number of complaints in the field of education also increased — and we promptly respond to each case. We also actively cooperate with local self-government bodies. We send recommendations, explanations, and support language initiatives. For example, we advised the Dnipro City Council to introduce a moratorium on the public use of Russian-language cultural products — and the council adopted a corresponding decision. This was an important step. A Russian song today is a trigger for most Ukrainians, and we must protect our information space.

Responsibility exists, but it is most effective when it transforms into linguistic legal awareness and mutual respect. This is what we strive for.

– Are there mechanisms to ensure the language rights of people with disabilities, particularly sign language users?

Yes, and this is a very important area. Ukrainian sign language is not an auxiliary tool, but a full-fledged language of the deaf community of Ukraine. The law clearly recognizes this. Article 23 of the Law "On Ensuring the Functioning of the Ukrainian Language as the State Language" guarantees its support, development, and training of interpreters.

Unfortunately, in real life, the situation is still far from ideal: not all TV channels have sign language interpretation, and not every institution has an interpreter. This means that some citizens still do not have equal access to information and services.

However, we also have positive dynamics: a draft law on Ukrainian sign language has already been registered in the Verkhovna Rada, which details the mechanisms for its integration into education, culture, and the administrative sphere. Its adoption will be an important step towards a truly inclusive language policy in which everyone can freely use the language, be heard, and participate in community life.

– The media often mentions "language patrols". Does anything similar exist in Ukraine? And what is a real alternative to such a practice?

This phrase appeared back in 2019 — it was launched by Russian propaganda, trying to intimidate Ukrainians with "punitive language formations." This is a typical disinformation technique — to present language protection as oppression.

The phrase "language patrol" itself sounds threatening, Soviet-like. Let's compare: "language patrol" and "language inspector." The first is like a punitive squad, the second is like a specialist who helps. But even "language inspectors" are not provided for by law. There are no "patrols" in Ukraine.

Control over compliance with language legislation is carried out only by the institution of the Commissioner — within the framework of the law, through official representatives in the regions. This is a civilized model based on dialogue, education, and mutual responsibility.

We cooperate with authorities, businesses, communities, and educators so that Ukrainian sounds natural and confident. An example is the story from Kharkiv, when a taxi driver refused to serve a passenger in Ukrainian. The reaction was legal, swift, and fair.

The alternative to "language patrols" is a conscious civil society and an effective state institution. The Ukrainian language does not need guardians — it needs partners. And the best "language patrol" is each of us who chooses Ukrainian every day.