Scientists find skull of huge ancient dolphin in the Amazon

Kyiv • UNN

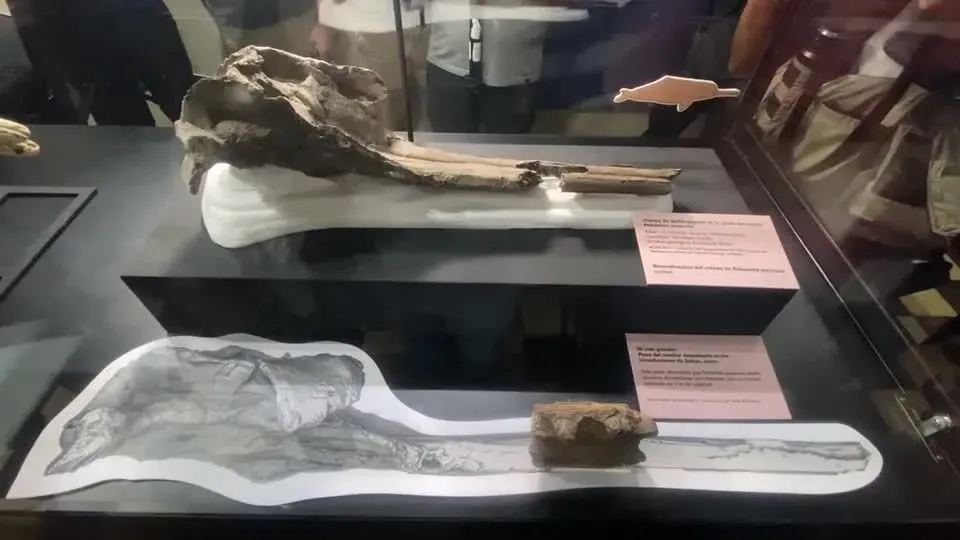

Scientists have discovered the fossilized skull of a 3.5-meter-long giant river dolphin that lived in Peru's rivers 16 million years ago, highlighting the risks faced by the world's remaining river dolphins today.

Scientists have found the fossilized skull of a giant river dolphin that is believed to have emerged from the ocean and lived in the Amazon rivers of Peru 16 million years ago. The extinct species was up to 3.5 meters long, making it the largest river dolphin ever found. This is reported by The Guardian, UNN reports.

Details

According to the lead author of a new study published in Science Advances, the discovery of this new species, Pebanista yacuruna, highlights the risks to the world's remaining river dolphins, all of which face a similar threat of extinction in the next 20 to 40 years. Aldo Benítez-Palomino said it belonged to the Platanistoidea family of dolphins, which are commonly found in the oceans 24-16 million years ago.

According to him, the surviving river dolphins were "remnants of once very diverse groups of sea dolphins" that are believed to have left the oceans to find new food sources in freshwater rivers.

Rivers are an escape valve... for the ancient fossils we found, and it's the same for all the river dolphins that live today

Benítez-Palomino discovered the fossil in Peru in 2018 while he was still a student. He is currently working on his doctoral dissertation at the Department of Paleontology at the University of Zurich, and says the research has been postponed due to the pandemic.

He first noticed a part of the fossil, a fragment of a jaw, while walking with a colleague.

"As soon as I recognized it, I saw the nests of teeth. I shouted, 'It's a dolphin'. We could not believe it.

Then we realized that this was not related to the pink dolphin of the Amazon River. We [found] an animal, a giant, whose closest living relative is 10,000 kilometers away in southeast Asia

Marcelo R. Sánchez-Villagra, director of the Department of Paleontology at the University of Zurich, said the find was intriguing. "After two decades of work in South America, we have found several giant forms in the region, but this is the first dolphin of its kind," he said.

According to Benítez-Palomino, the fossil was impressive both for its size and for the fact that it was not related to the river dolphins that now swim in the waters where it once lived.

A common problem facing river dolphins, including the closest living relatives of the fossils that swim in the Ganges and Indus rivers, is the imminent risk of extinction. Urban development, pollution and mining were key causes, he said, and had already led to the extinction of the Yangtze River dolphins.